"Unbelievable": Varan

Info

Also known as: Giant Monster Baran (Original Japanese); Varan the Unbelievable (U.S. cut); Varan - The Beast from the East (Brazil); Varan, the Giant Monster (France); Varan - the Monster from Prehistoric Times (Germany); Varan the Incredible (Mexico); The Giant Monster Varanus (USSR).

Director: Honda Ishiro. Screenplay: Sekizawa Shinichi, from a story by Kuronuma Ken. Director of Special Effects: Tsuburaya Eiji. Composer: Ifukube Akira.

Runtime: 87 minutes

Release Date: October 14, 1958

What’s It About?

Two researchers’ expedition in search of a rare butterfly species leads them to a remote village that worships the lake-dwelling god Baradagi. The explorers find their butterfly but wind up killed in a landslide, seemingly by Baradagi. One of them is survived by a sister, the reporter Yuriko (Sonoda Ayumi), who pursues the truth of her brother’s death with the help of one of the researchers’ peers, our leading man Kenji (Nomura Kozo). The expedition soon discovers that Baradagi, actually a giant aquatic lizard known as Varan, is very real. The military soon arrives to destroy the beast, but Varan unveils membranes between its limbs that allow it to glide into the air like a giant, reptilian flying squirrel. Having flown the coop of its mountain home, Varan makes its way toward Tokyo on a path of destruction!

Childhood Memories

Varan appears in one of the earliest pieces of Godzilla media I experience, the 1998 junior novel Godzilla vs. the Space Monster by the late Scott Ciencin. It’s Aunt Boopy’s first Godzilla-related gift for me after I have fallen in love with the ‘70s Hanna-Barbera Godzilla cartoon that aired on the English-language Cartoon Network channel in Iceland. In Space Monster, Varan is depicted as one of the ensemble of monsters who live on Monster Island and as a friendly rival of Rodan the giant Pteranodon. Rodan and Varan are among the many monsters that Space Monster introduces me to, right at the dawn of my interest in Godzilla.

I don’t see Varan on screen until 2002, when I watch the Godzilla film Destroy All Monsters, which features one of the largest monster casts in the entire series. This is a watershed moment, my first time seeing many of the monsters present in Space Monster on screen. But Varan himself has only a very brief cameo - it certainly leaves one wanting more.

So naturally, when I learn that Varan had his own movie in the vein of Rodan or Mothra, I’m curious about it. Thanks to Toho Kingdom, I learn that the American re-edit - which, to this day, I have not seen - is considered one of the worst American releases of any Toho monster film. As with The Mysterians, Tokyo Shock puts out a DVD release of Varan in 2005. I don’t recall Varan being part of my Christmas haul that year; 2005 was packed for me as far as Christmas gifts go, including the landmark tenth Land Before Time film and the long-awaited American DVD of 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars (in which Varan makes a brief stock footage cameo). But I definitely had the Varan DVD by sometime in 2006. I enjoy finally seeing this elusive monster in action at length…and I am fascinated by the most significant bonus feature included on the disc.

Varan was originally planned as a TV broadcast, and this version is included in lists of unmade or canceled kaiju film productions by Toho Kingdom and other sources. Many of these unmade films fascinate me, but the abandoned TV version of Varan is unique among the “lost” Godzilla-related films in that it actually exists! Or rather, an incomplete edit of this version was reconstructed from surviving materials for the Japanese DVD release, and now I get to watch this “unmade” film for real on the American release. Cool stuff!

I don’t find the human material in Varan terribly interesting, and for this reason, I think I actually end up watching the TV edit reconstruction more than the actual film: it certainly gets to the monster action sooner, though I mildly regret the absence of the butterfly plot element present in the final version. (I love butterflies, and am sad when the two researchers kill a specimen for collection. As far as I’m concerned, Varan was just avenging his fellow animals).

Equally, I was clearly attached to the film - or at least, the idea of the film - enough that I recall bringing the DVD along to Iceland, on one of my family’s yearly trips back to visit. That was the 2006 trip, actually the last regular visit we had. We didn’t go in 2007, and then the 2008 recession put a stop to our financial leeway to visit that often. We managed to eke out one more visit to mark the New Year’s transition from 2008 to 2009, and throughout the next decade, my mom would fly to Reykjavik for extended stays to work at the hospital that she’d worked at while we lived there from 1999 to 2002. I was able to visit once, during spring break from my sophomore year of college in 2018. My brother and I brought a friend each from our respective colleges, just down the road from each other in Burlington, Vermont.

My most recent time in Iceland was the brief layover I had in Keflavik International Airport the next year, in January, on my way to my semester abroad in Dublin. Before boarding the WOW Air flight from Iceland to Ireland, I was able to snag three Pylsur, Iceland’s signature brand of hot dogs. I took the nostalgic snack as a sign of much-welcomed encouragement for the new adventure I was nervously en route toward.

A couple of months later, WOW Air’s fortunes would turn out even more troubled and desperate than the production of Varan had been.

Analysis

Varan is a botch. This is less an assessment of its quality than of the facts. Because Varan was commissioned by an American television company for broadcast, the production started with filming in black-and-white and in the box-shaped 4:3 aspect ratio that was standard for televisions in the 20th century. But much like WOW Air would in March 2019, the television production company (allegedly AB-PT, a collaboration between ABC Television and Paramount Studios) went bankrupt, and the film’s status as an American television release fell through. Either because of this or as a separate development, Toho executives decided midway through production that Varan should see a proper Japanese theatrical release in line with their previous kaiju films.

There was one problem: because the film had a lower budget and a compressed shooting schedule, director Honda Ishiro, special effects director Tsuburaya Eiji, and their crews did not have time to reshoot the footage for the widescreen color format that had become de rigueur for Toho’s special effects productions just the year prior. Varan would remain in black-and-white, which wasn’t a deal-breaker; black-and-white was, through at least to the end of the sixties, considered more “respectable” than color film in Japan, where the latter was viewed by critics as a sign of a film’s pandering to mass audiences.

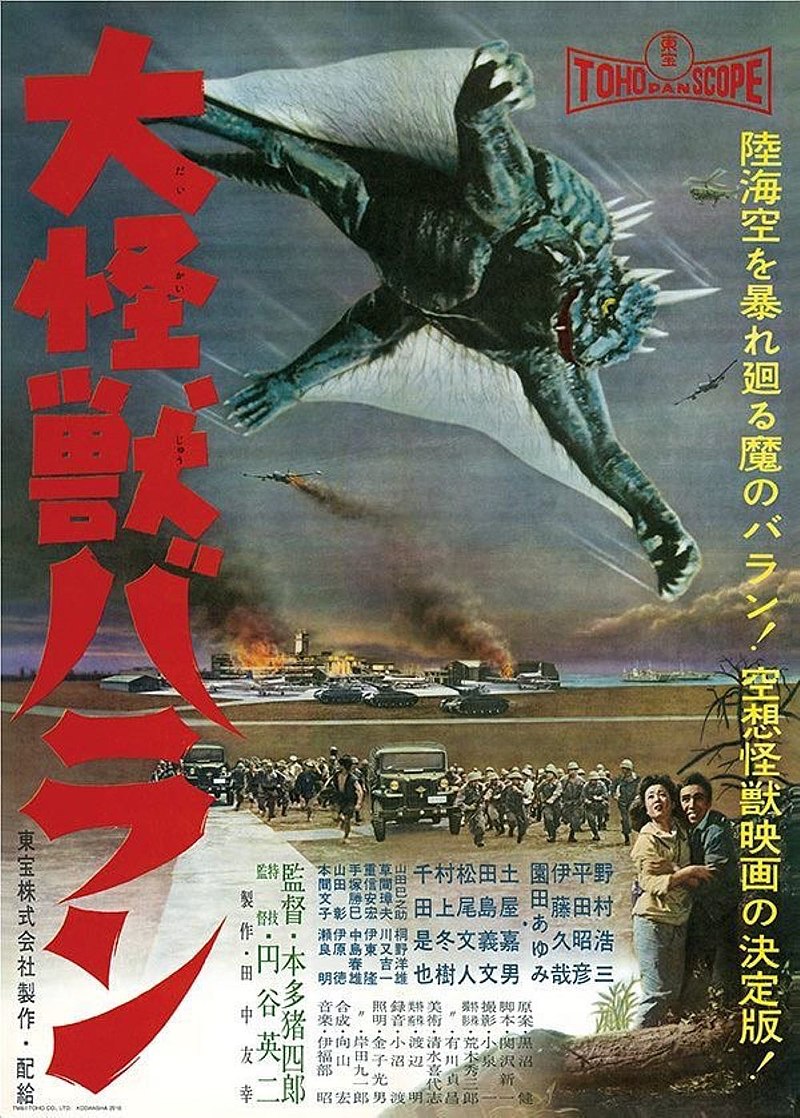

Instead, the real blow came when Honda was forced to crop the top and bottom off of the already completed footage in order to make it fit the ultra-wide TohoScope frame. This meant that footage designed to look good on square television sets (and that could have looked acceptable if released in that shape in theaters, as would have been the norm only two years before) looked awkwardly composed, zoomed in, and cramped on the rectangular image of the movie screen. Given that the additional spectacle offered by the ultra-wide screen was one of the selling points of filming TohoScope, the butchered cinematography was not a small problem. This was a problem exacerbated by the television-level budget, which meant that the level of spectacle on display was already reduced from Tsuburaya’s work for previous kaiju films. As though sheepishly admitting to what an aesthetic disaster Varan was, Toho released it with a “Toho Pan Scope” logo instead of the usual opening TohoScope banner.

The end result is an objective hatchet job of a film, what could have been a charming curiosity for the small screen sandbagged by its conversion for the big one. It was: commissioned as a generic product for what was surely viewed, then, as a lesser medium; based on a hastily-provided storyline from Ken Kuronuma, the novelist who had also provided the story for Rodan; assigned to Sekizawa Shinichi, a newly hired screenwriter and ex-animator who was not enthusiastic about being handed someone else’s story to adapt; shot in plain black-and-white in a way that fails to do much of interest with the format until the very end, when the cinematographers finally make decent use of dark shadows in the imagery; re-edited into a full feature from the television version while retaining its episodic plot structure; and finally dealt the indignity of the aspect ratio conversion. Whatever his feelings about the direction of his career, Honda Ishiro was not known to complain about the individual assignments he was given, which makes it all the more notable that he would later declare Varan a failure that he did not have the production circumstances to do any amount of justice to.

Indeed, what makes Varan notable is that it is the first Toho monster film that does nothing to advance the genre, instead serving as a greatest hits presentation of kaiju film tropes for a foreign market. Ironically, this makes Varan valuable as a tool for determining which ingredients, exactly, Toho thought constituted a generic version of their films circa 1958. We have:

A giant, prehistoric reptilian monster (Gojira, Godzilla Raids Again, Rodan).

A protagonist who’s a scientist of some type (The Mysterians, The H-Man).

An elder scientist role model who serves as a voice of knowledge and reason in the story (Gojira, Godzilla Raids Again, Half Human, The Mysterians, The H-Man).

Another scientist, played by Hirata Akihiko, whose invention is repurposed to defeat the monster (Gojira).

A remote village whose inhabitants worship the monster, leading to conflict between tradition and modernity as concerns Japanese society (Gojira, Half Human).

The monster attacking Tokyo, which had previously only happened outright in Gojira (though set in Tokyo, The H-Man never actually features its human-sized monsters razing the city).

That last bullet point is worth elaborating on. Having previously featured a variety of locations for kaiju to attack - Osaka, Fukuoka, Mount Aso, Mount Fuji - Varan marks the first return to a previous location for its kaiju’s main rampage. It’s obviously the case that Tokyo is the most well known Japanese location to the rest of the world, such that the phrase “giant monsters attack Tokyo” is an understandable generalization of the daikaiju genre - but even so, it is Varan that sets the trend of returning to Japan’s capital, such that the generalization becomes a serviceable one rather than a misleading description based only on Gojira.

In among its checklist of previous kaiju elements, Varan even introduces a whole new element that will become a recurring trend: a main character who’s a journalist, in this case Yuriko, the female lead. Overall, though, what’s striking about the film is just how little is fleshed out in it. All of the returning tropes listed above feel “got through”, with none of them being explored in any depth. The superstitious kaiju-worshipping villagers, offensively stereotyped like the ones in Half Human, aren’t even egregious to the same degree because of how little the script examines the conflict between the urban outsiders and their unfriendly hosts. You just have the lead, Kenji the researcher, ungraciously declaring that he doesn’t respect the villagers’ traditions or believe in their god (with a staggering lack of social tact); and the hostile village elder (Sera Akira) growling about how Baradagi will eat all those who trespass on its land, and refusing to permit a rescue party to search for a missing boy because it would bring about the god’s wrath. There’s no substance to the conflict, just a scenario recycled from Half Human, which itself had ripped its antagonistic tribe from King Kong. Meanwhile, the ostensible emotional connection that Yuriko and Kenji have to the story - the deaths of her brother and his friends - never comes into play, with the characters serving as a perfunctory plucky damsel and brave leading man, respectively. Most strikingly, there is no moral or ethical dilemma surrounding the weapon used to defeat Varan. The new bomb, intended by its inventor Dr. Fujimara (Hirata) for use in rock clearance during dam construction, is a simple plot-solver that can defeat the monster, with Fujimara evincing no reflection whatsoever on the repurposing of his creation. The film’s narrative is as bare bones as a kaiju film could be without ceasing to function as a story altogether.

This essay has been extremely critical of Varan, so it’s worth reiterating that this is intended as a diagnostic analysis of the film, and not a condemnation; the worst that could be said about Varan in a qualitative sense is that it is lackluster and dull in a largely painless fashion, not that it is an abomination against cinema (and certainly, the existence of the American theatrical edit demonstrates how much worse the project could have been). And there is a significant point of redemption for the film: Varan himself. It’s true that the creature is not as impressive a creation as Godzilla or Rodan, but Varan is distinctive enough to still stand on his four limbs. There’s more than a hint of the Creature from the Black Lagoon in the design, befitting Varan’s aquatic nature, which distorts his saurian features enough to set him apart from Godzilla or Anguirus; his lumpy, bumpy skin texture and single row of thin, pale spines down his back similarly set him apart from his fellow giant reptiles. And Varan’s “wings” that allow him to glide, his most unique trait, are both a striking visual in their own right and different enough from Rodan’s wingspan to not feel like a copy. That Varan’s gliding ability is not demonstrated more than once in the film may count as one of its disappointments, but the mid-film scene in which the previously grounded lizard spreads his membranes and soars away stands as both its best moment and as an endearingly memorable image. Any committed fan of monster movies in general will surely acknowledge that many times, the monster is by far the most successful element of an otherwise lacking film; that Varan falls into this pattern is no great shame in the grand scheme of the genre, especially considering its production circumstances. If nothing else, the indelible image of a giant lizard defying expectations and taking to the air demonstrates that even when they were at their lowest ebb, the Toho kaiju crew was still capable of producing genuine movie magic.

(A word on the TV edit reconstruction, since there’s not a lot of English language information on it out there as far as I’m aware. The TV version of Varan was slated to be three episodes, but only two are present in the reconstruction included in the Japanese and American DVD releases. The extant episodes correspond pretty exactly to the last two-thirds of the theatrical film, with Varan already revealed as of the start of the “first” episode, which leads me to believe that the audio tracks for the planned second and third episodes were all that survived, with the tracks for the first episode lost to time. Additionally, the footage in the reconstruction is unfortunately cropped like it is in the theatrical release, suggesting that even the surviving material absent from the theatrical version was so edited prior to being discarded from the final cut. The two episodes aren’t too different from the corresponding sections of the film, other than the absence of the theatrical cut’s biggest addition, an ocean battle between Varan and the Japanese navy - which is, in fact, the first “proper” monster versus battleships fight in any of these films.)

Return to the master We Call It Godzilla index here.

Comments

Post a Comment